Jun 20, 2025

The bond market rarely makes headlines — but it should. It sets the tone for everything from interest rates and currency values to stock prices and investor confidence. Traders may shout about equities, and analysts may obsess over central banks, but beneath it all, it’s the bond market that calls the shots. In this article, we’ll explore how bond yields shape financial markets, steer central bank policy, move currencies, and even tilt the playing field between growth and value stocks. Understanding bonds isn’t just for fixed income specialists — it’s essential for anyone navigating today’s markets.

Bonds are debt instruments issued by governments, municipalities, and corporations to raise money. When you buy a bond, you’re effectively lending your money to the issuer in exchange for periodic interest payments (called coupons) and the return of your principal at the end of a predetermined period (maturity).

If you’re new to bonds or need a refresher, we’ve created a separate article explaining the fundamental features of bonds — like maturity, coupon rates, credit ratings, and yield. We recommend reading that first for a strong foundation.

Here, we go beyond the basics. We’re zooming in on bond yields and how they influence other major asset classes.

The yield curve is one of the most powerful tools for reading the bond market — and, by extension, broader market sentiment. It’s a graphical representation showing the yields (returns) on bonds of the same credit quality but different maturities, typically government bonds.

Normally:

Short-term bonds have lower yields.

Long-term bonds offer higher yields to compensate investors for tying up money over longer periods.

So a ‘normal’ yield curve has an upward slope.

But here’s where things start to get really interesting — and admittedly, a bit more complex.

The shape of the yield curve is not static; it changes constantly in response to evolving market expectations about key economic variables, particularly inflation, economic growth, and monetary policy.

These shifts in the curve — whether it’s steepening, flattening, or inverting — offer rich insight into how investors perceive the future. While these movements aren’t perfect predictors, they are widely monitored by economists, strategists, and central bankers alike for the clues they provide.

Steep Yield Curve: Optimism, or Concern?

A steep yield curve typically occurs when the difference between short-term and long-term interest rates is large — meaning long-term yields are significantly higher than short-term ones. This is often interpreted as a sign that investors expect stronger economic growth or higher inflation in the future. Why? Because if the economy is likely to expand rapidly, or if inflation is expected to rise, lenders and investors will demand higher yields on long-term bonds to compensate for the risks associated with holding those bonds over time.

This type of curve is often seen during the early stages of an economic recovery, when central banks keep short-term rates low to stimulate growth, but markets begin to anticipate that stronger activity will eventually prompt rate hikes down the line.

However, it can also signal concern: if inflation is expected to surge beyond the central bank’s control, the steep curve may reflect fears of policy tightening or loss of purchasing power.

A flat yield curve suggests that the gap between short- and long-term yields has narrowed. This can occur when short-term rates are rising (perhaps due to central bank hikes) while long-term yields remain relatively stable, or even decline. When investors see little difference between yields on 2-year and 10-year bonds, for example, it may reflect uncertainty about the economic outlook, or a belief that future growth and inflation will be subdued.

A flat curve doesn’t always indicate trouble ahead, but it often reflects a transitional phase — either as the economy begins to cool after a period of expansion, or as markets digest mixed signals about future risks and policy direction.

Some investors view it as a sign that the current policy stance is restrictive enough to slow down momentum, even if a full-blown downturn isn’t imminent.

The inverted yield curve is perhaps the most talked-about version. This happens when short-term yields rise above long-term yields — a dynamic that runs counter to the norm, where investors typically demand more yield to lend money over longer horizons.

Inversion is widely seen as a recession warning, and for good reason: historically, most U.S. recessions over the past several decades were preceded by an inversion in key parts of the curve, especially the spread between 2-year and 10-year Treasury yields.

The logic behind this signal is that when short-term borrowing costs rise too high — often due to aggressive rate hikes by the central bank — while long-term growth and inflation expectations weaken, it suggests the economy may be heading into a slowdown. In effect, the bond market is pricing in a policy mistake: the idea that tightening has gone too far and will eventually force the central bank to reverse course to stave off a downturn.

The economic theory is a often a solid guide, but interpreting the yield curve — especially when using it as a potential predictor of economic recessions — is not an exact science. While the yield curve has historically been viewed as a fairly reliable forecasting tool, it’s far from infallible, and there are notable exceptions where its signals haven’t played out as expected. A particularly striking example of this emerged in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Following the unprecedented economic disruption caused by the pandemic in 2020, the U.S. economy experienced a rapid and highly unusual recovery phase, driven in large part by expansive fiscal stimulus, historically low interest rates, and a surge in consumer demand once lockdowns eased. Amid this backdrop, inflation began to rise significantly, prompting the Federal Reserve and other major central banks to shift gears from ultra-accommodative monetary policy toward aggressive tightening, including a series of rapid and substantial interest rate hikes.

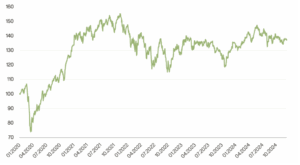

As a result of these actions and evolving market expectations, the 2–10 year segment of the U.S. Treasury yield curve inverted — meaning the yield on the 2-year Treasury rose above the yield on the 10-year Treasury. This inversion, which traditionally signals that investors expect weaker growth or even recession in the future, first occurred in mid-2022 and persisted for an unusually long stretch of time — nearly two full years, making it one of the longest inversions in recent history.

Historically, such an inversion has been one of the most closely watched harbingers of an economic downturn. In fact, every U.S. recession over the past several decades has been preceded by an inversion of the yield curve, particularly the 2–10 year spread. So naturally, when this inversion appeared and deepened, economists, analysts, and investors alike sounded the alarm and braced for a looming recession.

But here’s the twist: the widely anticipated recession never materialized, at least not in the time frame or severity that many expected.

Despite persistent inversion, the U.S. economy demonstrated remarkable resilience. Consumer spending remained robust, job creation continued at a steady pace, corporate earnings held up better than feared, and GDP growth — while slower than the post-COVID boom — stayed in positive territory. Even inflation, though sticky and problematic, began to ease without the economy plunging into a deep contraction. In other words, the economy defied the textbook scenario that an inverted yield curve is supposed to foreshadow.

This experience served as a potent reminder that while the yield curve can provide valuable insights into market expectations and macroeconomic risks, it’s not a crystal ball.

The post-pandemic era introduced a wide range of distortions — fiscal stimulus on an unprecedented scale, supply chain shocks, labor market shifts, and rapidly changing monetary policy — all of which combined to create conditions that broke the mold of typical economic cycles. The inverted yield curve reflected investor uncertainty and pessimism about the future, but it did not fully capture the unique structural dynamics that were at play.

Despite these imperfections, shifts in the yield curve remain one of the most influential and widely followed indicators in all of finance. Changes in its shape offer a real-time window into investor sentiment, expectations for the Federal Reserve’s next move, and the broader macroeconomic climate. Portfolio managers, traders, central bankers, and financial journalists all look to the curve as a barometer of risk appetite and a guidepost for potential turning points in the economic cycle.

Ultimately, while no single indicator should ever be used in isolation, the yield curve deserves its reputation as a powerful market signal — especially when interpreted with nuance, context, and an understanding of the unique forces driving the economy at any given time.

Government bonds, particularly the US’, are considered low-risk or even risk-free assets. Their yields, therefore, serve as the benchmark against which all other risk assets — like equities — are priced.

Yes, there’s growing criticism about whether government debt is truly ‘risk-free’ given exploding debt levels and rising anxiety about the sustainability of the trend. But for now, bond yields still underpin most risk models across asset classes.

Equity prices are largely determined using discounted cash flow (DCF) models, which estimate the present value of future earnings or revenues. These models rely on a discount rate, and that discount rate is closely tied to — guess what — bond yields.

When bond yields rise, the discount rate increases → the present value of future earnings drops → equity prices fall.

When yields fall, the discount rate declines → future earnings look more valuable → equity prices rise.

This dynamic explains why central banks use rate cuts and bond-buying (aka quantitative easing) as tools to boost asset prices and stimulate economic growth. It’s called policy transmission: monetary policy influences bond yields, which ripple through to stocks, housing, currencies, and consumer behavior.

Growth vs. Value Stocks

Not all equities are impacted equally by bond yield changes:

- Growth stocks — especially in tech — tend to suffer more when yields rise. Their valuations depend heavily on future earnings.

- Value stocks — like those in industrials or energy — often hold up better in high-yield environments, as their returns are tied more to present performance.

It’s worth noting that central banks don’t always control bond yields as much as they’d like to.

Take the example of the Fed’s rate cut in September 2024. Despite the central bank lowering rates, yields went up. Why? Because investors didn’t buy the story. Many believed the Fed was acting prematurely, cutting rates while the economy was still holding strong. This skepticism sent bond yields higher, not lower.

This is a reminder that bond yields reflect market expectations, not just central bank policy. And when investors disagree with the central bank’s direction, they vote with their feet — driving yields in the opposite direction.

Let’s shift gears to currencies.

Bond yields play a critical role in shaping the relative value of currencies. After all, currencies reflect the health of their underlying economies — growth, inflation, interest rates, and investor confidence. Yields serve as a shortcut to assess all these variables at once.

Take two countries: Country A has high yields, Country B has low yields. All else equal, investors will want to move capital from B to A to benefit from the higher return, boosting Country A’s currency.

This leads us to the world of carry trades.

The Carry Trade: Profiting from Yield Differentials

A carry trade involves borrowing in a low-yielding currency (like the Japanese yen or Swiss franc) and investing in a high-yielding one (like the Brazilian real or Turkish lira). As long as exchange rates remain stable, this strategy delivers consistent returns.

But there’s a catch: carry trades can reverse violently. When risk sentiment turns, investors rush out of high-yielding assets, leading to sharp currency depreciation.

In theory, over the long term, currencies from high-inflation, high-yield countries often depreciate to compensate for their risk. But in the short term, the opposite may happen, as rising yields attract capital inflows. Hence, carry trade remains one of the most popular FX trading strategies!

Bond yields move first. Stocks and currencies tend to follow.

When you see equity prices dropping or a currency suddenly depreciating, ask yourself: What are bond yields doing?

- Are yields rising due to inflation or hawkish central bank expectations? That could explain stock declines.

- Are yields falling due to recession fears? That could trigger equity volatility but support defensive currencies like the yen or Swiss franc.

Understanding bond market trends gives you an edge — whether you’re a long-term investor, a trader, or simply trying to make sense of the headlines.

- Bond yields influence the pricing of nearly every other financial asset.

- The yield curve tells you about future growth, inflation expectations, and central bank credibility.

- Bond yields serve as the foundation of equity valuation models.

- They shape currency markets via interest rate differentials and carry trades.

- And most importantly, they often move before stocks and currencies do — making bonds a leading indicator.

So the next time you see headlines about rate cuts, yield spikes, or central bank decisions, remember: the bond market is the first domino. And understanding that market gives you powerful insight into what comes next.

Ipek Ozkardeskaya is a senior market analyst. She has begun her financial career in 2010 in the structured products desk of the Swiss Banque Cantonale Vaudoise. She worked at HSBC Private Bank in Geneva in relation to high and ultra-high net worth clients. In 2012, she started as FX Strategist at Swissquote Bank. She worked as a Senior Market Analyst in London Capital Group in London and in Shanghai. She returned to Swissquote Bank as Senior Analyst in 2020.